The Past and Present of Beijing's Siheyuan 北京四合院的前世今生

English 英: Beverly Cheng · Chinese 中:已不在穆里的根叔

Photography: Ziyu Zhuang of BUZZ/BÜRO

「建築是具有自治性的,故而融入『當地文化』不應該是建築的唯一追求。在中文語境裡,我們經常把文化(culture)和文脈(context)混淆,文化是流動的,然而實質上建築更多情況下是在地的,作為建築師,我們能掌握更多的是關於文脈層面。」屢獲殊榮的年青建築師莊子玉在設計其北京鼓樓七號院的新工作室時,就巧妙地糅合了傳統文化、當代建築和在地設計的精髓,實踐 「以人為本」的建築理念,為北京老城內的四合院注入新生命。

三千年歷史旳北京,擁有二千一百五十萬人口,於過去三十年間迅速發展,絕對是一個令人驚歎連連的都會。RSAA/Bür 首席建築師暨合伙人莊子玉,於2010年毅然回流到他度過童年的北京,並創立了莊子玉工作室。北京急促發展帶來眼花繚亂的銳變,他都一一看在眼內。

「在過去的三十載,北京經歷了戲劇性的轉變。從前我到親友家串門子,都是在胡同裡的。今天卻只剩下不到 1% 的人口住在這些老房子裡。」——莊子玉

Knowing that he wanted to move his architecture studio from a lacklustre glass tower in Guomao financial district to something more inspiring, Ziyu turned to Beijing’s Old Town because of its timeless character and proximity to downtown. Finding a suitable historic building proved to be challenging because of their scarcity. Presently, there are less than 20,000 properties available, with some larger, luxury properties going for a whopping 2 billion RMB (198 million CAD).

傳承風土文化的特色、在地的空間設計,加上市中心就近在咫尺的便利,莊子玉認為在保育胡同原有建築特徵,和注入嶄新意念的衝擊下,必能湧出更多創意和靈感。所以他決定,把工作室從欠缺活力的國貿玻璃商廈,搬到富空間感、生活氣息皆截然不同的四合院裡。這些編寫着歷史的建築,隨北京經年的規畫發展,倖存的已不到兩萬戶。別小看它們老舊,物以罕為貴,面積較大而保存優良的,叫價二十億人民幣也不誇張(折合約一億九十八百萬加元)。

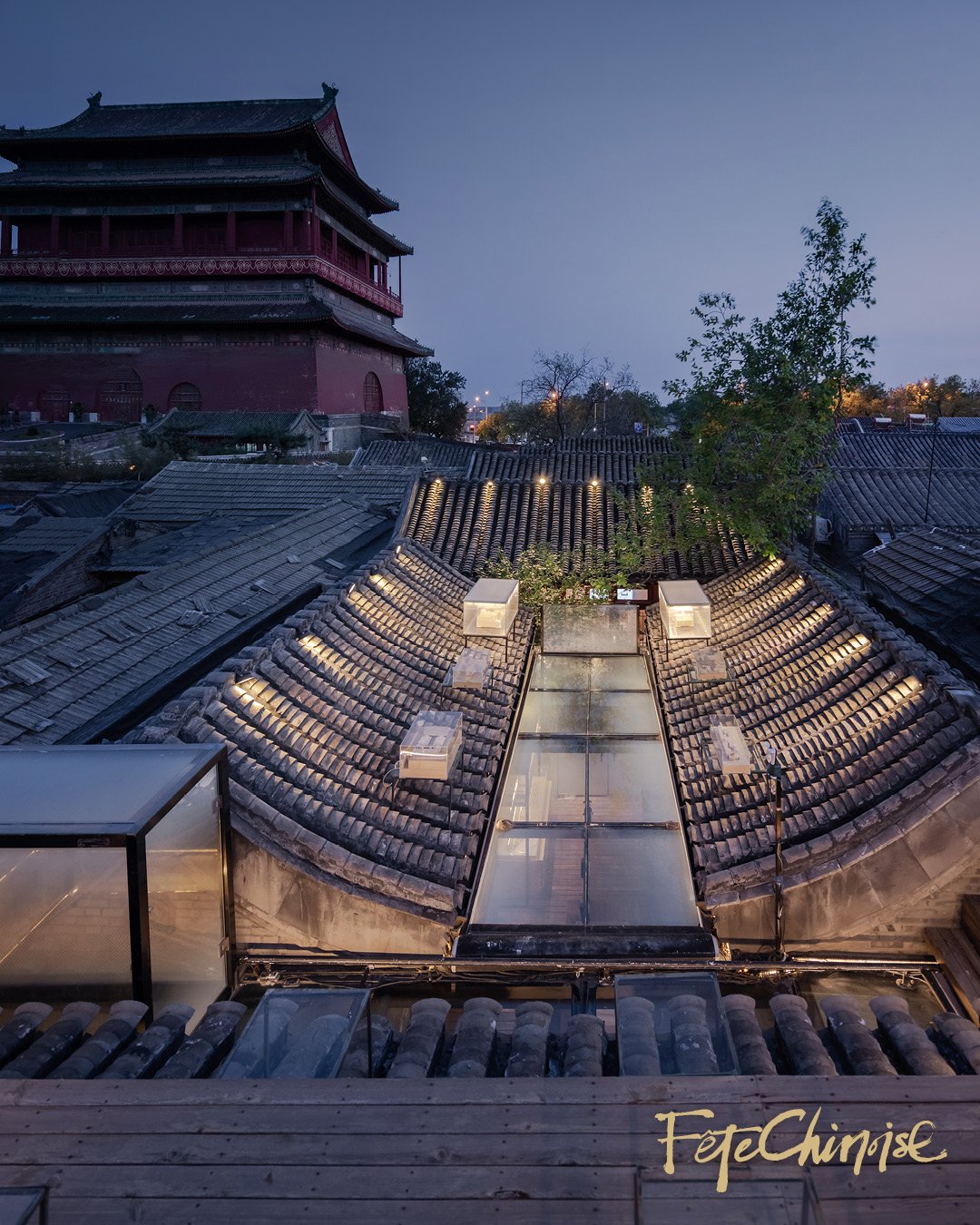

When he first set foot in the courtyard-siheyuan in Dongjiaogan Hutong, which would become Courtyard No. 7 of the Drum Tower, Ziyu gasped at seeing two of Beijing’s 600-year-old landmarks, the Bell Tower and Drum Tower, overhead. Views of the nearby historic landmarks inspired Ziyu to incorporate more of the outdoor areas and build upwards, creating a terraced rooftop where his team could connect and socialize, or simply admire unobstructed views of the surrounding neighbourhood.

莊子玉第一次踏進這座鼓樓七號院,抬頭看到眼前已聳立了六百年的地標鐘樓、鼓樓和周遭饒有歷史的建築,便決心把新工作室 「向上發展」,同時加設廣闊的戶外空間。開通不同界面的空間平台、將房與房之間連繫起來,也是他的建築哲學。

This innovative new glass addition atop the traditional structure is groundbreaking, and brings new meaning to the courtyard building. Traditionally, rooftops in historic Chinese buildings were not used as a functional space. They were decorative features that had symbolic meaning, showing the prestige of the family residing within its stone walls. By transforming the rooftop into a social space, Ziyu has adapted it for contemporary use. His human-centric design approach continues in his treatment of the disjointed Northern, Eastern and Western wings of the courtyard by connecting the areas with a glass atrium that serves to both expand the space and ensure there are communal areas where different teams can meet. An additional floor was also added to the Southern wing to create more space for gatherings and meetings.

以往的中式設計,屋頂不會被視為可用的空間。屋簷上一般只有瑞獸裝飾,簷角前端用以固定瓦片的瓦釘裝飾,也是家族名聲的象徵。全新設計用上了一系列創新的玻璃加固,把中庭區,東、西、北三房連在一起,與他以人為本的哲學接軌,不單讓視野變得更遼闊,亦令工作和活動空間變得更廣。

Sponsored by FERRIS WHEEL PRESS

“Unlike Western architecture, in which the door, windows and everything is fixed, the walls in traditional Chinese architecture have no supportive function and you can design the building more easily.”

While studying at Columbia University, Ziyu was fascinated at how the fluidity of Chinese language and culture affected design. “The way you speak really influences your perception of reality. Chinese language is very flexible, and you can easily change the order of your grammar and switch up the same words to form completely different meanings. How we speak also informs how we live and adapt easily” recalls Ziyu. “Unlike Western architecture, in which the door, windows and everything is fixed, the walls in traditional Chinese architecture have no supportive function and you can design the building more easily.”

當年,仍在哥倫比亞大學裡攻讀的莊子玉,不懈地研究靈活多變的中國文化和語言,如何為設計觀點帶來不同層面的影響。他補充說:「以中文溝通時,說話的方式,往往能反映一個人對於現實的看法。中文文法千變萬化,稍微換一下字詞組合或排列次序,意思也截然不同。西式建築概念較中式的呆板,不怎麼能在既有的框架上作出改動。而傳統中式建築裡,牆壁的作用並非是為支撐房子,因此也能作出不同變化。西方建築的門、窗和其他基本配件為了要維持平衡的支撐,在環環相扣的情況下就不容隨意作出改動。」

Image: Turning Red, Disney+

The change in scenery has also made a mark on the team’s design direction, with the studio taking on more projects that adapt traditional Chinese buildings for modern use. For Ziyu, he sees this shift as evidence that his team is being inspired through their personal experiences with the space and architecture, rather than incorporating Chinese elements for merely aesthetic value or artifice.

團隊設計鼓樓七號院的方向,重點顧及如何能巧妙地,讓中式元素融合於現代的用途中。讓他感到高興的是,團隊懂得憑藉各自生活上不同體驗而有所啓發,不只單純側重於美學上的琢磨,這呼應了莊子玉「以人為本」的理念。

“I don’t see Guomao as modern and new or the Old Town traditional and old. They’re part of the same evolving city that changes in scale. My choice to move to a hutong was not about looking backwards at history. It’s about looking at humanity, at how humans live,” says Ziyu. By adapting historic courtyards to contemporary times, he believes the buildings suitable for modern use because they are on a human scale and add to the overall diversity of the city.

他接着說:「我不認為以『現代/新派』來形容國貿是正確的;也不贊同舊城區就必定是『傳統/老舊』。兩者皆處於同一個時代巨輪中,以相同的步伐往前邁進。我選擇搬到胡同,並非旨在緬懷歷史,而是近距離的了解真實的人性和生活方式。按照『以人為本』的設計方向而活化的歷史院子,切合當代的需求。新與舊磨合產生的火花,亦能替都市添一分色彩。」

“Diversity in architecture is the belief that everyone has a say. It comes from the people at the bottom who dictate how they want to live in a city, not from the top down (...) Architecture should come back to people’s lives, how we live and what our needs are.”

In recent years, Beijing’s Old Town is undergoing a massive renewal project with many inhabited hutongs being cleaned up and renovated. “It’s a pity that there are renovations to the Qing Dynasty buildings and they’re trying to restore it back to the way it was 200-300 years ago. For me, this is nonsense,” opines Ziyu. According to Ziyu, before the Beijing Olympics in 2008, the city was a destination for emerging designers. In the Old Town, underground punk culture flourished, and many of the seemingly dilapidated courtyards were alive with artist workshops and hidden bars where creatives would meet. The area was known as “Beijing’s Brooklyn” because of its bubbling creative energy. Today, remnants of this subculture barely remain.

“Diversity in architecture is the belief that everyone has a say. It comes from the people at the bottom who dictate how they want to live in a city, not from the top down” says Ziyu. This is not the way things are done typically in Classical Modernist city zoning that designates specific locations for offices, residential areas and shopping zones. Architecture should come back to people’s lives, how we live and what our needs are.”

北京舊城區這幾年正處於一個修復胡同的的大型規劃當中。「我為此感到可惜。要修復至二三百年前清朝時候的原貌,對我來說是毫無意義的。」莊子玉這麼想,因在2008年北京奧運以前,北京曾是個設計師的天堂,地下音樂等搖滾文化在舊城區內發展得非常蓬勃。大部分破舊失修的院子能重活過來,靠着各式工作坊及隱藏酒吧的林立,吸引各路藝術家到來,因此更被喻為「北京的布魯克林」,代表着對這股朝氣勃勃的創意力量的認同。今天再看,曾經的次文化不復再,就連殘留物都相繼被抹煞。

訪問完結前一刻,莊子玉慨嘆:「再好的建築產品都會被淘汰,所以要對未來趨勢進行結合。一個典型的新都市設計,理應依據住在鄰里社區裡你我他的需求作規劃文脈,讓都市內各行各業都得到最佳的持續發展機會。」

SPonsored by FERRIS WHEEL PRESS

The 2026 Lunar New Year celebration by the Toronto Symphony Orchestra honoured Chinese culture through music and dance. Led by conductor Carolyn Kuan and host Dashan, the evening featured renowned pipa virtuoso Wu Man, pianist Ryan Huang, and a lineup of captivating programmes.