Unfolding a Botanical Tapestry: Exploring the Intricate Design of Vancouver’s Dr. Sun Yat-Sen Classical Chinese Garden 從中山公園看蘇州庭園之美

English 英: Frank Abbott · Chinese 中:Translated by Maggie Ho

Photography: The Vancouver Chinese Garden & Erik Andersen, Butter Studios

As featured in 2024 Fête Chinoise Design Annual

Photography: Erik Anderson, Butter Studios

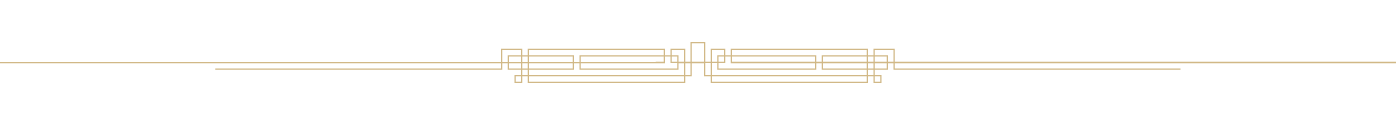

Vancouver’s Dr. Sun Yat-Sen Classical Chinese Garden is one of a small number of what are known as traditional scholar’s gardens. When it opened 38 years ago, it was the first classical garden built outside China in the country’s most sophisticated style, which was developed centuries ago in the southern city of Suzhou.

What is it that makes this Chinese scholar’s garden so special?

Its many visitors have attested that it is extremely beautiful and profoundly peaceful. Those who want a deeper understanding will find the complexities of its design and its connections to traditional Chinese culture extremely rewarding. As a long-time docent of the garden, I personally am enchanted by it. Ever since I became a member of the garden when it opened in 1986, my favourite part has always been a bench inside the Musician›s Gallery in a quiet corner of the Scholar’s Courtyard. Its tranquility allows me to imagine that I’m not in the city at all, while the architecture of the Study is pleasing to the eye. And even when the garden is busy, people don’t always notice the door leading to it from the south courtyard. It’s best in the spring when the peonies and magnolias are in bloom.

江南園林甲天下,蘇州園林甲江南。 蘇州園林以小巧骨子,氣韻生動,為人所頌讚。 雖說一方水土養一方人,想不到在加拿大溫哥華境內有一片靜土,讓人可以感受「居士高蹤何處尋,居然城市有山林」的寫意逸趣。

位於加拿大卑詩省溫哥華華埠內的中山公園,建於1986年,是首個中國境外修建,完全仿傚蘇州園林風格而建的中式庭園。 公園每年吸引約十萬多人次參觀,遊人除了欣賞其靈秀景致,對當中精妙佈局及所蘊藏之深邃意境,均讚嘆不已。

Photography: Erik Anderson, Butter Studios

History

The Dr. Sun Yat-Sen Classical Chinese Garden came about by accident after protests by Vancouver residents torpedoed a plan to ram a freeway through Chinatown in the 1970s, which would have demolished the historic community. Out of the controversy came the construction of the Chinese Cultural Centre, a welcome but belated recognition of the contributions that Chinese immigrants have made to the city, along with the desire to include a Chinese garden in the plans for the new centre. The inspiration for constructing a garden came from Vancouver architect Joe Wai (1940 –2017). His drive and his generous collaboration with Wang Zuxing of the Suzhou Garden Administration, chief architect of Vancouver’s garden, produced a masterpiece on one-third of a one-acre city block, which is echoed in the adjoining public park that occupies the other two-thirds.

The governments of China and Canada supported the idea, but the impetus came from the Chinese community and the public at large, which raised close to $6 million for its construction. It opened in April 1986 after 13 months of work by 52 skilled artisans from the Suzhou Garden Technical Expert Team, who brought a thousand tonnes of material to construct it. They used the same kinds of traditional hand tools that would have been employed 500 or more years ago.

Photography: Erik Anderson, Butter Studios

The classical style chosen for the “scholar’s garden” originates in the southern city of Suzhou — roughly 60 kilometers west of Shanghai — and is widely recognized as the finest expression of Chinese garden art. Suzhou gardens go back nearly 2,000 years, but they reached their apogee during the Ming (1368–1644) and Qing (1644–1911) dynasties. Today, there are over 100 classical gardens in Suzhou — nine of them on UNESCO’s World Heritage List, as is the city itself.

Civilization and Nature

A scholar’s garden harmoniously combines three apparently contradictory philosophical schools of Chinese thought. Daoism assumes that meaning is to be found in the search for individual freedom and a closer understanding of the natural order by rejecting the trappings of civilization. Confucianism takes the opposite approach: Meaning is to be found in fostering good human relations in a well-run civilized society. Buddhism, which came to China from India roughly 2,000 years ago, argues that a focus on the visible world, which is an illusion, prevents us from finding true meaning.

Photography: Erik Anderson, Butter Studios

In the garden, the philosophical and aesthetic assumptions about the relationship between humanity and nature combine the ethical virtues of Confucianism (self-watchfulness, leniency, sincerity) and the value of civilization with the humane ideals of Daoism (compassion, moderation, humility) and its celebration of the natural world, as well as with the mental and spiritual self-discipline of Buddhism (ethical conduct, mental discipline, wisdom). While individual scholars emphasized different aspects of these philosophies according to their own temperaments, this syncretism showed how we should get along with each other and what humanity’s relationship with the natural world could and should be.

For over 1,500 years, these scholars defined Chinese culture. China was unique in that it employed an examination system to select candidates to help the emperor administer the country, bypassing and eventually replacing the feudal nobility. The system was perfected in the Song Dynasty (960–1279), though it roots went back even further. Based on a humanist curriculum, the exams tested students on the Four Books written before 300 BC (the Analects of Confucius, the Doctrine of the Mean, the Great Learning, and Mencius) and the Five Classics (the Classic of Poetry, the Book of Documents, the Book of Rites, the I Ching, and the Spring and Autumn Annals — all of which were even older), as well as the Zuo Zhuan, an ancient narrative history and the primary text that helped educated people understand China’s earliest history. Later, the works of Song Dynasty Neo-Confucian scholar Zhu Xi (1030–1100) were added. Whether or not a scholar also became an official, the system produced generations of scholars imbued with the same philosophical outlook.

Photography: Erik Anderson, Butter Studios

歷史源由

中山公園的建造,本身亦有一段故事。 一九七零年代末,溫哥華市政府曾經一度修建片打街和奇化街連接路(Pender-Keefer Diversion),該項目因為涉及清拆唐人街範圍而受到當地居民大力反對,後來政府將該片用地改為興建中華文化中心及中山公園,以表揚華裔移民對當地社區的貢獻。

Photography: Erik Anderson, Butter Studios

項目得到加拿大三級政府、中國政府,以及當地華人社區鼎力支持,籌得接近六百萬元經費。 外園免費公園(Dr. Sun Yat-Sen Park)由著名溫哥華建築師韋業祖 (Joe Wai, 1940-2017)與園林建築師Don Vaughan合作設計而成;園內另設收費公園「逸園」(Dr. Sun Yat-Sen Classical Chinese Garden),由蘇州園林行政部總建築師Wang Zhu Xin 率領旗下部門「香山幫」工人負責興建。 經過長達十三個月,從中國蘇州運送了過千噸物料,同時由中國政府派出五十二名蘇州庭園林專家及工匠,以傳統工藝技術先在蘇州建造、拆裝,再運至溫哥華重組建造。 工程於1985年開展,1986年4月23日落成,剛好迎上當年在溫哥華舉行的世界博覽會Expo 86 。

Visiting the Garden

A scholar’s private garden is the smallest of three types of classical Chinese gardens (the others are grandiose imperial gardens and natural landscape gardens). Scholars’ gardens are based on a few simple principles. Humanity is embedded in the natural order. Inspiration and pleasure are to be found in mountains, water, and forests. As the wise and celebrated Zhu Xi wrote, “It is not the case that man, as the being possessed of the highest intellect, stands alone in the universe. His mind is also the mind of birds and beasts, of grass and trees.”

In the small space of one-third of an acre, Vancouver’s scholar’s garden — designed by Wang Zuxing — contains the natural world in miniature. Five dozen kinds of plants inform us of the variety in that natural order. These plants include pine trees, bamboo, Japanese maples, gingko, peonies, boxwood, holly, magnolias, rhododendrons, camelias, azaleas, yew, Chinese roses, junipers, and mondo grass. Its essential elements — the placement of plants, water, and rockeries — are laid out to give visitors continuously changing and varied insights into the natural world.

Photography: Lorraine Lowe

As Mr. Wang noted, the rocks, water, and plants in the garden are meant to imitate nature, but for a designer to do so successfully, he or she “must first appreciate and understand the beauty of the natural world (…) Rational skills are then applied to this understanding and nature is recreated like a three-dimensional Chinese landscape painting.” A scholarly garden is a creation of civilization that reaches out to connect with nature, a balanced and harmonious blend of the natural and the manmade.

文人園林 情趣兼並

「逸園」佔地1430平方米,其中建築面積496平方米,佔整個中山公園的三分一面積,全園按照蘇州園林風格而建。 相對中國北方富麗堂皇、氣勢磅礴的皇家園林,蘇州園林以小巧、淡雅、寫意、精緻為主要特色,崇尚自然,藏而不露。 蘇州園林的歷史可追溯至西元前春秋時期,於晉唐年代逐漸發展,至宋元明清期間為巔峰。 明清時期,蘇州成為中國最繁華的地區,私家園林多達二百處,遍佈古城內外;現存於中國的蘇州園林只有五十多處,包括被列入世界文化遺產名錄,合稱「蘇州四大園林」的滄浪亭、獅子林、拙政園及留園。

Photography: Erik Anderson, Butter Studios

古代蘇州園林的造園者,多是因官場失意被貶的士大夫、亦有愛好詩書的商賈士紳。 他們將個人的審美及閒情志趣寄託於私人天地中,創造出人與自然和諧共處的隱世庭園。 在有限的空間內,通過疊山理水,栽植花木,配置園林建築,形成充滿詩情畫意的文人寫意山水園林,因此蘇州園林又稱「文人園林」。

Four different elements make up a Suzhou garden: traditional buildings (pavilions, covered walkways, terraces, lookout platforms), plants, water, and rocks. In addition, they are surrounded by walls to shut out city noise and to allow relaxation. Human architecture is meant to blend with the garden’s natural elements, not to dominate them. By not calling attention to themselves, the white walls and black-tiled roofs of buildings, walls, and corridors symbolize humanity’s need for harmony with nature. They serve as neutral surfaces to reflect the natural elements. Despite the windows and doors, there is no “indoors” versus “outdoors”: Buildings and their furnishings are meant to carry the sense of the exterior scenes into the sensibilities of their occupants. The inside looks to the outside for meaning and relaxation while reinterpreting it within its philosophical parameters. In that sense, it is a space where civilization and nature coexist in harmony in the belief that natural landscapes can be further beautified through the application of the creative and skilful craftsmanship of man.

遊園賞景 托物寄意

Photography: Jeremy Lee

中山公園內「逸園」,總設計按照風水和道家陰陽平衡學說,強調和諧有序,順應自然之道。 園林外圍以白牆黑瓦迴環曲折地包圍整個花園,隔絕了牆外的喧囂,凸顯公園為繁囂都市中的一片靜土。 園內依照傳統蘇派園林布局:假山搭配一潭靜水,倒映出四方天地。 工程師巧妙地在只有三尺水深的湖底鋪上深綠色的瓦片,利用一片翠綠造成視覺上深邃幽黯的錯覺,此舉同時可保護池魚免受飛鳥的啄食。 湖邊的假山、迴廊小徑,刻意選用紋理、形狀不同的太湖石及鵝卵石拼砌而成。 漫步其中,細看亭台樓閣、小橋流水、花鳥蟲魚、曲徑奇石,移步換境,就像閒逛於江南古鎮中,景外有景,樂趣無窮。

The garden has four main areas: the entrance courtyard and China Maple Hall; the central area around a pond with a miniature mountain topped by a viewing pavilion; a double corridor and Jade Water Pavilion; and the Scholar’s Study and courtyard.

Dominating the China Maple Courtyard is a dramatic three-metre-tall Taihu rock. These large limestone rocks full of holes and wrinkles look like natural or abstract works of art, and are essential features of classical Chinese gardens. They are prized for looking lean (sou) or pierced (tou) or leaking (lou) or wrinkled (zhou). Placed near water and vegetation, they symbolize strength and hardness, while water represents yielding and softness. But they also remind us of the yin and yang principle that dichotomy resides in everything. If rock can be changed by water, it also contains elements of softness and yielding, while apparently passive water can demonstrate elements of strength and hardness. The rocks catch the eye because of their varied shapes frozen in time, while the water is always changing.

Photography: Erik Anderson, Butter Studios

Located at the north end of the garden, the China Maple Hall (“Hua Feng Tang”) is one of two furnished rooms — the Scholar’s Study is at the other end of the garden — that connect the scholar’s civilized world with the natural elements in the garden. It faces south onto a large courtyard patterned with flower blossoms made from pebbles and roof tiles. From here one sees, from right to left, an island of limestone rocks topped by a viewing pavilion, a pond at the center of the garden, and a double corridor leading to the Jade Water Pavilion.

The Hall, with its Ming-style chairs arranged as if people are sitting down for tea and conversation, is a place to receive visitors and welcome them to the garden. It displays references to the three philosophies in the garden: Confucianism, popular Daoism, and Buddhism. They echo the symbolic references or rebuses scattered or sprinkled throughout the garden — for instance, the bats on the drip tiles that go all around the garden are a play on words, since “bat” has the same sound (“fu”) as “good fortune.”

園內主建築為「華楓堂」,內分三進,內堂有四根香楠木為主柱,跟園內其他建築一樣,全以傳統榫卯嵌合法,不用任何鋼釘。

除了工藝非凡,園內各處亦可盡見造園者利用花木托物言志的造景手法:「四宜書室」書齋外分別種有合稱「歲寒三友」的松、竹、梅,表達對高尚品格的嚮往;「華楓堂」門外則分別種了代表中國的銀杏樹和代表加拿大的楓樹,寓意中加兩國友誼長存。

A small bridge on the east side of the courtyard leads to a rock island with a winding path ascending a miniature “mountain” built up of Taihu rocks. On top sits the small Colourful and Cloudy Pavilion (“Yun Wei Ting”), a place for a scholar to rest while viewing the scenery. (Because of the uneven path, the ascent to the top is closed to the public.) Two pine trees — as well as begonias, peonies, boxwood, holly, and bamboo — cling to the sides of the mountain.

Photography: Natalie Choo

Nearby, a double corridor leads to the Jade Water Pavilion, which features an east-facing circular wooden arch with carvings of plums, orchids, bamboo, and chrysanthemums. An equally elaborate square arch with the same floral motifs faces west. Symbolically, the circle and square motif found in several places in the garden represents the nature–civilization dialogue. The circle, standing for fulfillment, oneness, and perfection, is the shape of the unknowable, Heaven. In contrast, the square’s straight lines and sharp corners represent Earth, law and regulation, the realm of man, a stable structure, and firm ground. It represents what can be contained and measured, which is to say civilization. The message here is harmony and balance between nature and civilization, between one’s emotional and intellectual sides. Likewise, the curved patterns of the China Maple Courtyard balance the straight lines of the southern courtyard and the Scholar’s Courtyard at the south end of the garden.

The final section of the garden is the Scholar’s Courtyard and Study, separated from the rest of the garden with its own wall. The study’s name plaque reads “Study Suitable for the Four Seasons” (“Si Yi Shu Wu”). Like the other structures in the garden, it is built on the traditional pillar-and-beam method with mortise-and-tenon joints. Most of the pillars and horizontal beams are of fir from Jiangxi province, although four each in the China Maple Hall and Scholar’s Study are of now-protected nan wood from Sichuan province. Camphor wood rafters support terracotta tiles on the inside of the ceilings and the curved roof tiles outside. These tiles, which require over two dozen separate steps to produce, came from the Suzhou Lumu Imperial kiln, active during the Ming dynasty and still in operation today, though at a much-reduced scale. Furnished simply, the Study contains a desk that faces south to the plants and Taihu rocks in the courtyard, which is meant to have an atmosphere of peace and elegance.

Photography: Erik Anderson, Butter Studios

Conclusion

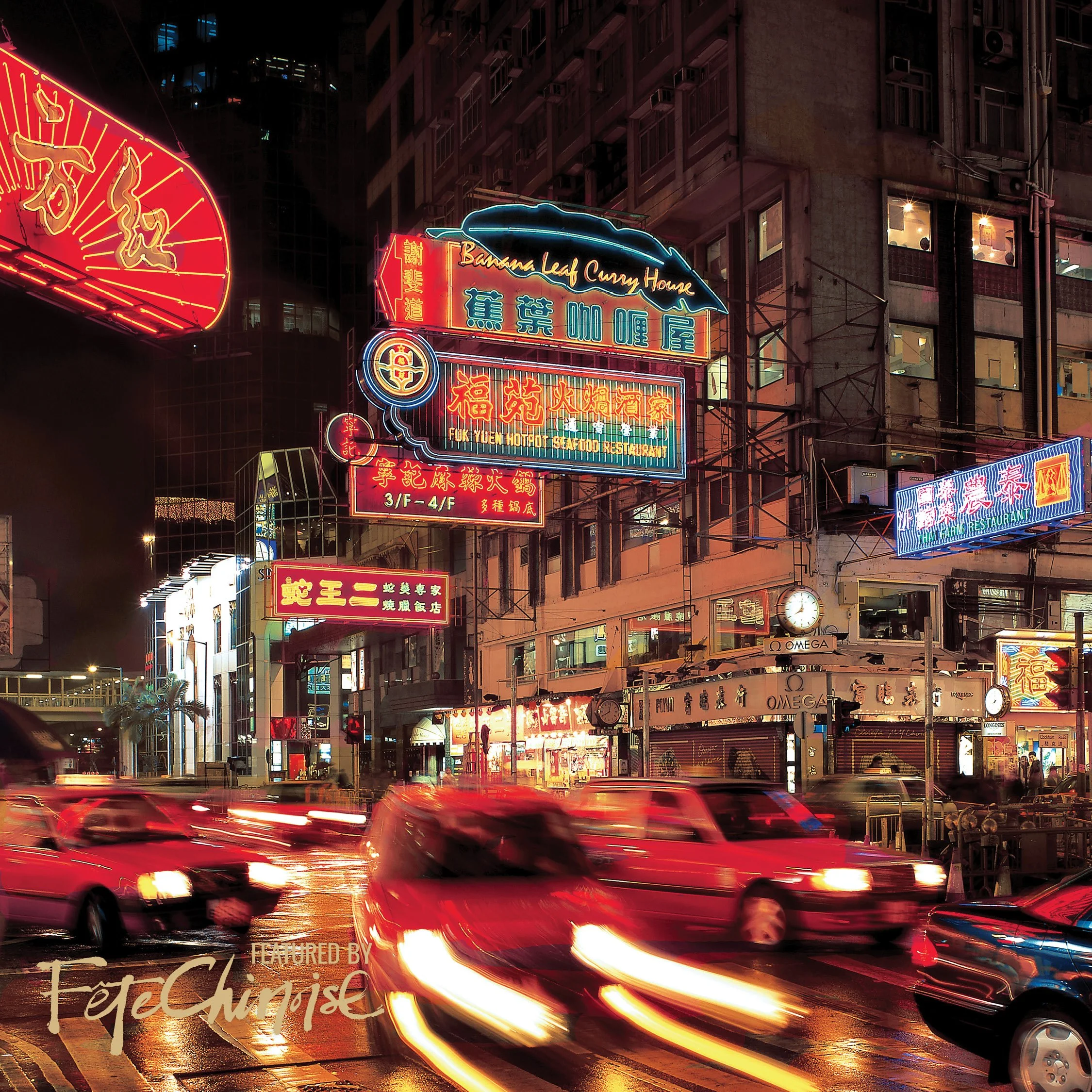

In this small corner of the city, and on the very block where Chinatown began in the 1880s, Chinese Canadians can feel the affirmative power of the rich traditional culture their ancestors brought to this country in the Dr. Sun Yat-Sen Classical Chinese Garden. It is a bridge for understanding between people of all cultures. The garden is one of Vancouver’s treasured cultural institutions, a hub for arts and culture, a museum, a community resource, a leading tourist attraction, and an educational operation. Its school programs attract students from the area’s schools. Its cultural programs, such as the popular “Enchanted Evenings,” feature musical performances from many cultures.

中山公園建園至今已差不多四十年,園內一磚一瓦、一草一木,裡裡外外,展現出江南文化的精髓,令人身處異鄉,猶如置身江南美景中。 更難得的是,該園除了憑藉四季美景吸引八方來客,近年更積極舉辦春節廟會、中秋晚會、書法、武術、舞龍舞獅等豐富文化活動,其角色早已從公園轉化成博物館,社區資源中心、旅遊景點和教育中心,兼負文化傳承的重任,妙不可言。

The artist-in-residence program introduces new artistic voices to the community. The Xiao program, as its name implies, expresses the value of filial piety by bringing area seniors to the garden in a safe social space. On major holidays such as the Mid-Autumn Festival and the Lunar New Year, the garden opens its doors to the community for celebration. It has been playing an active role in preserving the viability and livability of Chinatown.

But ultimately, the garden is a place where people can escape — however briefly — from the pressures of the commercial world surrounding us and enjoy a profoundly peaceful relationship with nature.

All in all, a very special place.

Photography: Erik Anderson, Butter Studios

In Chinese culinary tradition, the Longevity Peach Bun (or Shoutao), holds a special place. Often found at birthday banquets for the elderly, this delightful treat is more than just a delicious dessert—it is a symbol of health, prosperity, and a long life. With its unique appearance and cultural significance, the symbolic bun continues to be a staple at celebrations as traditions are passed down generations of families in Asia and in diasporas around the world.