Cutting Through Tradition: Yang Shih-yi’s Intricate Paper Art 因捨而得的剪紙哲學

English 英 & Chinese 中:Maggie Ho

Photography Provided by 楊士毅 - 聚合果工作室

As featured in 2024 Fête Chinoise Design Annual

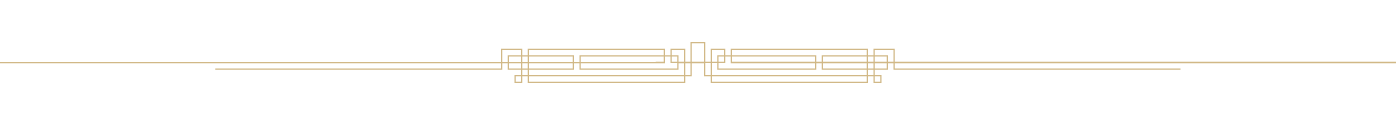

德國蔡司:光之祝福(2023)

In a world where artists often boast about their exceptional and distinctive creations, Taiwanese paper-cutting artist Yang Shih-yi stands apart with his humility. Unlike many artists who speak loftily about their works, Yang describes himself as merely a storyteller, messenger, and servant to serve others' needs. He even goes as far as to say, “The arts might not even be significant.” His primary concern is whether his works will inspire a sense of joy and well-being in people.

Yang's ethos of giving is akin to the philosophy of “subtraction of life” that he learned through years of paper cutting. “Paper cutting is a form of subtraction,” he explains. “One must cut something out to create skeletons or spaces for a beautiful, bigger picture. Once you try paper cutting, you'll notice there's always leftover paper. When we achieve our goals, it's essential to remain humble and grateful, as our accomplishments are rooted in the support we receive from others. And during times of difficulty, it's important to view the experience as illuminating the path for future achievements.”

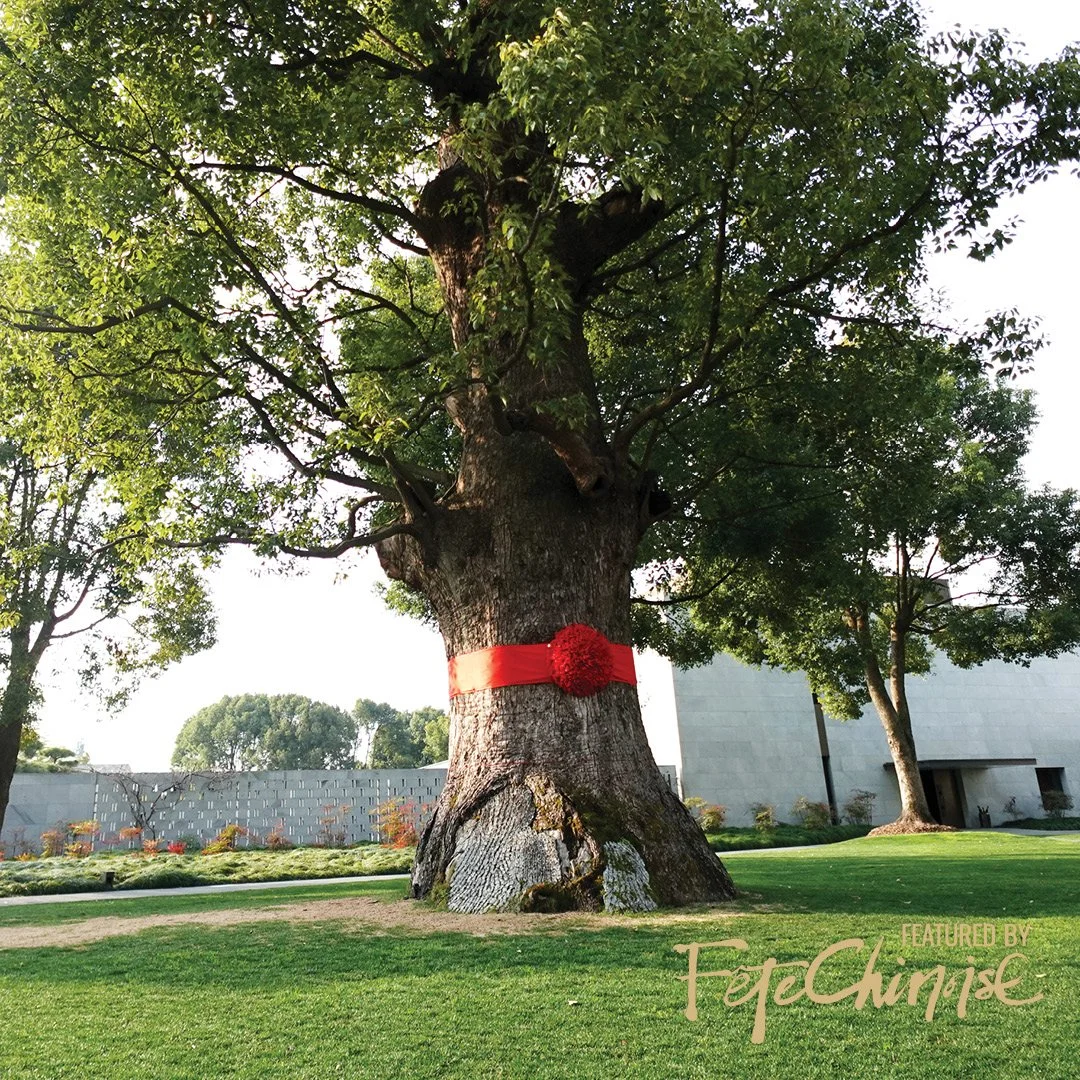

衛武營國家文化藝術中心春節裝置:繁花盛開的祝福(2021)

一般從事藝術創作的人,都熱衷於表現自己「創」造了甚麼與別不同、卓爾不凡之作。 台灣剪紙藝術家楊士毅卻謙卑得像個虔誠的信徒,不斷強調自己作為說故事的人、訊息傳播員、服務他人的角色,甚至坦言「藝術沒那麼了不起」;就正如他從剪紙領悟得來的「減法哲理」,從痛苦中解脫,拋開執念、放下自我,創作出最原始真實、美好善良,令人幸福滿滿的作品。

This philosophy, rooted in paper cutting, reflects Yang's life journey. Previously acclaimed as a successful photographer and movie director, having won the Golden Horse Film Award, Yang found himself unfulfilled by his pursuit of accolades. “I have won over a hundred photography, film, and commercial awards, but I still did not feel happy,” he says. “All my photography works are in black and white, expressing my frustration, anger, and sadness.” Yang's isolated, friendless, and unhappy childhood drove him to work extremely hard.

“My father owed a lot of debts. My family was so poor that I had to keep working to earn lots of money to pay them off. I couldn't help but wonder why I had to face all this hardship and when it would end. My upbringing taught me how to read people and seek their approval. I love telling stories. But after some time in the profession, I began to long for something more.”

百富:一心一藝專注的光輝(2022)

放下,無止境的追求

「剪紙就是減法,是在捨去之中創造擁有的過程,每當你剪掉一些,圖像就更顯露一些,所以必需學會放下、失去。 大家可以試一下剪紙,完成一幅剪紙,看着旁邊被剪下的紙碎,你會知道,擁有的時候不要太得意,那是因為有人願意退到一旁,才讓你擁有這一切;失去的時候也不要太悲傷,要去感受生命藉由失去要為你顯露的訊息。 剪紙也是學習平衡看待生命的方式。 」

台北燈節:你的初心是最美的光(2020)

It wasn't until Yang discovered a piece of handcrafted paper cutting that he became captivated by the art form. “Initially, I sought to acquire another skill to equip myself for more job opportunities,” he explains, “yet the art itself is so pure and beautiful that I felt compelled to pursue it.”

Yang's life underwent a significant shift in 2007 when he became part of the Wanderer Project, a subsidized program offered by the Cloud Gate Dance Theatre. His journeys to rural China profoundly transformed him.

As Yang immersed himself in agricultural districts such as Ansai in northern Shaanxi, Ku Shu-lan's vibrant paper-cut artworks seized his attention. Despite facing poverty and illiteracy, Ku Shu-lan, a former area resident, had dedicated herself to the ancient craft of paper cutting, captivating Yang with her masterpieces. Her commitment earned her the title of “Master of China Folk Art and Crafts” from UNESCO, which recognized her exceptional efforts in preserving and promoting traditional Chinese art forms. Even after her passing in 2004, Ku Shu-lan's legacy continues to inspire artists worldwide, Yang among them.

台北燈節:雞年起家(2017)

楊士毅從剪紙悟出的「減法哲理」多少亦是他的人生經驗之談。 困苦的童年,家中債台高築,令他不得不拼命工作賺錢;刻苦的經歷,磨練了他早熟敏銳的觸覺、習慣取悅他人及愛說故事的個性。 在接觸剪紙之前,他早是個出色的攝影師、導演、編劇,於國內外得過超過一百多個獎項,更曾入圍金馬獎。 即使如此,楊士毅坦言早期的自己在不斷的追名逐利中,從未找到真正滿足,「以前的我,太多憤怒、怨恨跟不滿,作品都是黑白沒有色彩的編導式攝影,大部分時間都在訢說自己心中的苦悶、痛苦。 」直至當他偶然間看到一個充滿喜悅溫暖的剪紙作品,心中頓時澄明如鏡:「我要的不是藝術,我要的是幸福!」

德國蔡司:光之祝福(2023)

“Her passion was so pure,” Yang observes. “Her life wasn’t easy, yet she didn’t dwell on the past or criticize her surroundings. She found joy in crafting within the beautiful world of paper cutting, continuing to do so for the people she loved.”

Yang's reflection on Ku Shu-lan's simple yet profoundly moving works led him to feel ashamed and to realize that art should serve the purpose of connecting people, after all.

Spreading Positivity through Paper Cutting

The art of paper cutting in China has a rich history dating back to the 2nd century CE, coinciding with the invention of paper by Cai Lun. Primarily practiced by women in rural areas, the art form involves red paper to create festive and auspicious images displayed on doorways, windows, walls, and greeting cards. These intricate works carry symbolic significance, as they traditionally served in religious rituals and depicted deities. Often crafted with red paper, a symbol of prosperity in Chinese culture, these artworks typically feature auspicious imagery and lucky characters such as Fu (福, blessing) and Xi (囍, double happiness). According to Yang, paper cutting is a means of conveying wishes to others while also preserving personal aspirations. For those who cannot write, they express themselves through patterns made by cutting paper. For example, cutting a flower vase (平 píng) symbolizes peace (平安 píng ān), while a lotus flower (蓮 lián), which phonetically resembles the phrase “having children for generations” (連生貴子 lián shēng guì zǐ), carries similar connotations.

客家新瓦屋冬季裝置藝術展:伯公的祝福(2015)

黃土高原上最原始的藝術

為了學得一門手藝,也為了克服個人的恐懼,楊士毅參加了雲門所舉辦的「流浪者計畫」,走訪陝西、雲南、西藏等多個地方,親眼看到陝西大娘庫淑蘭活在最貧瘠之地,但單純地投入在剪紙世界內。 「她的生活並不容易,可是她從不跟過去斤斤計較,也不跟環境討價還價,只是單純地為所愛的人剪紙。 」楊士毅親眼見證那些售價不足五元人民幣的剪紙,出自婦女之手用以幫補家計,為家人帶來幸福。 「那些作品都很簡單、很美麗,簡單得令人無法虛偽,無法偽裝。 在它們面前,所有高深的偽裝都變得原形畢露。 」看著那些原始那些原始、美麗、處處洋溢幸福的剪紙作品,令他不得不反省自己對工作、對藝術、對創作的態度。

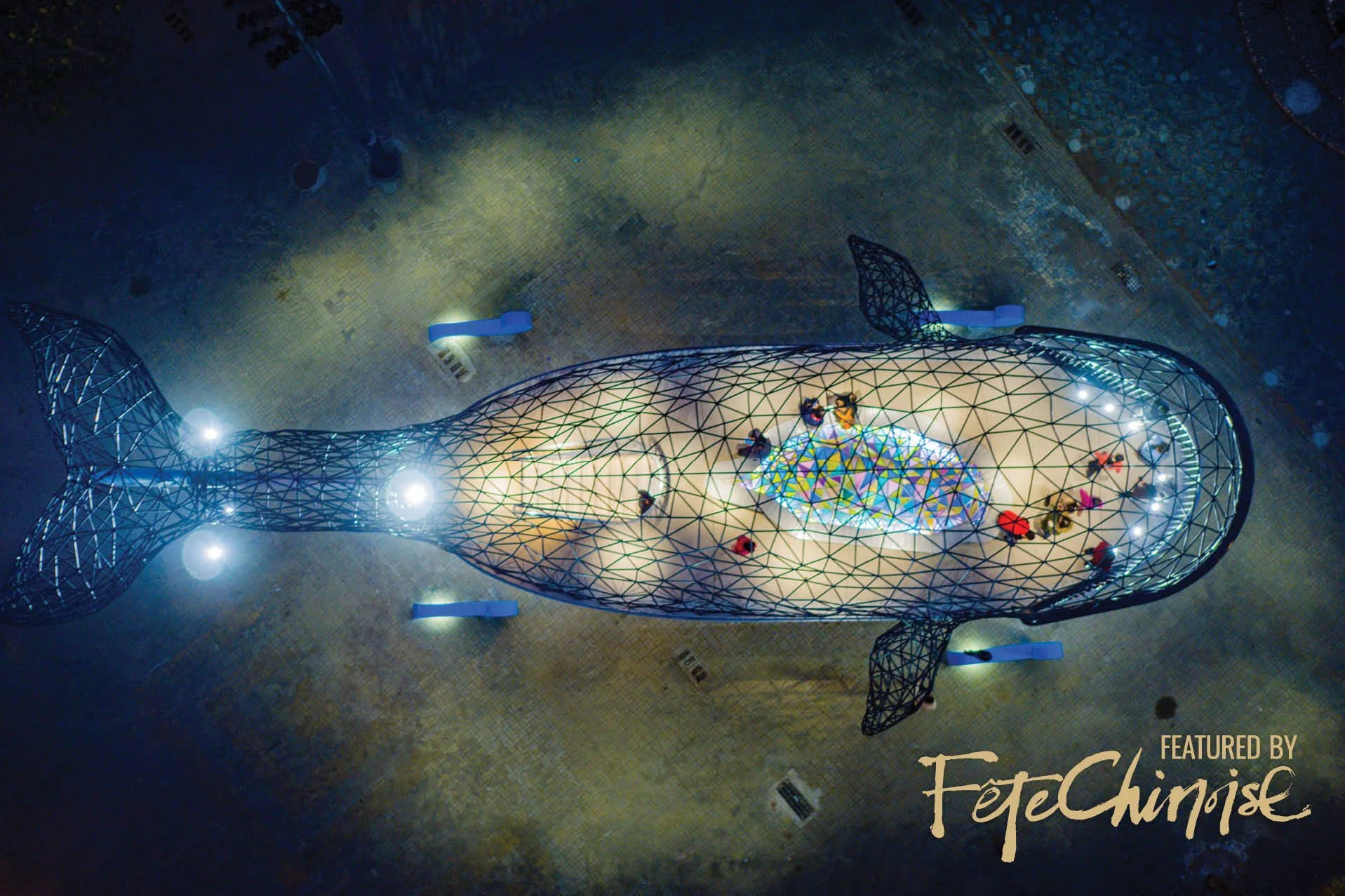

扇形鹽田:生命之樹(2023)

Unlike traditional paper-cutting art, which emphasizes intricate and delicate lines to showcase exceptional skill, Yang's creations boast a plump and vibrant aesthetic. They frequently portray cheerful characters, offering a contemporary twist on ancient craftsmanship and folktales. For Yang, these artworks transcend mere expressions of creativity; they serve as potent vehicles for meaningful communication, elevating paper-cutting into a conduit for conveying emotions and expressing love. “I'm not striving to revolutionize or stand out,” he says, “but rather to foster connection.”

剪紙是最古老的傳意工具,擁有二千多年的歷史,據說起源於中國漢代,當時的人們開始使用簡單的工具剪刻竹簡和紙張,後來蔡倫發明造紙術,剪紙藝術亦應運而生。 未受教育、不懂書寫的婦女尤其依賴圖象傳達意思,她們以剪紙傳遞祝福,或是表達心願;例如在花瓶上貼個「平安」字樣,又或剪個鏤空蓮花圖,貼在牆上或窗户上,取其「連生貴子」之意。

衛武營國家文化藝術中心春節裝置:繁花盛開的祝福(2021)

In one striking example, Yang reimagines the traditional Chinese folktale surrounding the Chinese New Year's Nian beast. Traditionally, this fearsome creature wreaks havoc, causing destruction and suffering among the people. To ward off the Nian beast, people traditionally set off firecrackers and display red decorative strips with auspicious messages. However, in Yang's 2015 paper-cutting masterpiece, he presents a remarkable reinterpretation: he transforms the once menacing Nian beast into a charming and endearing round-shaped figure. This new portrayal aims to communicate a message of familial unity and reunion as the New Year approaches.

百富:一心一藝專注的光輝(2022)

“Paper cutting and spending time with families are valuable cultural practices that deserve preservation,” Yang says. “While our culture has historically relied on fear as a means of enforcement, I believe fear cannot propel us forward in a positive direction. Love and care, on the other hand, can. By transforming the Nian beast into a positive figure that encourages children to reunite with their families, we evoke a more receptive response from people. The endearing character resonates with everyone, leaving a lasting impression and reinforcing the message conveyed in the artwork.”

藝術為分享愛的訊息

有別於傳統剪紙作品的繁複精細,楊士毅的剪紙作品中常出現線條圓潤諧趣的角色,而且所用到的媒體亦不限於紙。 他解釋自己「突破傳統,不為創新,而是為完成溝通。 」例如在傳統春聯或揮春的習俗,是用紅紙、炮杖嚇跑那吃掉孩子的年獸。 這個古老的傳說對現代人來說 ,早已變得陌生甚至不合時宜,剪紙工藝及團年的習俗卻是值得保留的。 楊士毅在作品《年獸》中為年獸換個新形象:胖胖圓圓,造型可愛,提醒在外的孩子在春節趕回家,與家人共聚天倫。 「生活不需要太多的恐懼,恐懼會令人失去嘗試、進步的信心。 」換個形象,換個角度,把原本生人勿近的怪物,變成愛心滿滿,傳遞正能量、人見人愛的吉祥物。

客家新瓦屋冬季裝置藝術展:記憶水稻田(2015)

Public Engagement Vital for Completion of Art

Yang finds solace in the enduring ability to connect with others, bridging cultural and linguistic divides. “Despite our apparent differences, we all yearn for love and connection,” he says.

Guided by this profound belief, Yang channels his creativity into a diverse range of heartwarming projects, from meticulously crafted silhouette letter paper and Chinese New Year gift boxes to expansive stencil art installations and outdoor public artworks.

For Yang, the true essence of his artistic endeavours lies in the joy they bring to those who experience them. “When you give out candies,” he says, “the candies themselves are not the focus; it's the smiles on the children's faces that truly matter.”

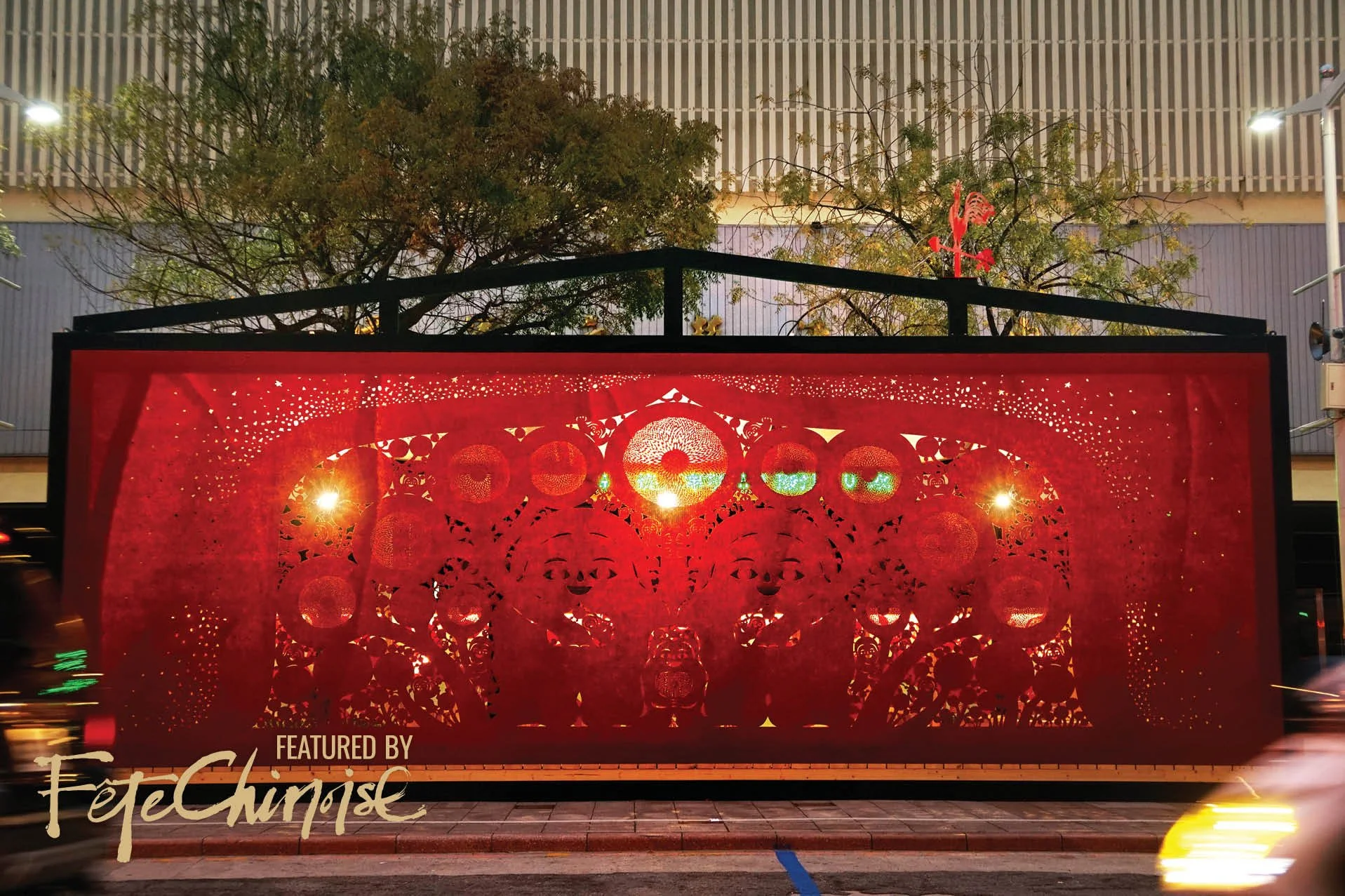

大魚的祝福(2019)

楊士毅的作品,不受創作媒體、語言及文化所限,無論是鏤空信紙、新年禮盒、户外裝置作品,都充滿窩心訊息。 「就如送給小孩的糖果,要記得最重要的不是糖果,而是小孩收到糖果後的笑臉。 藝術也是如此,只是方法,重要的是人的幸福。 」從台北燈節《你的初心是最美的光》(2020)、 台南安平《大魚的祝福》(2019)、台南市將軍區扇形鹽田《生命之樹》(2024)、台北101蘋果旗艦店開幕作品《有閒來坐》(2017),他都切身處地為客戶、服務對象及社會設想。 「這個世界沒有義務要完成你個人的夢想。 藝術沒那麼了不起,藝術是完全是為了人而存在。 我們要去服務別人的需要。 」除了承接大大小小的藝術創作設計工作,他更會受邀開課教授剪紙。 說穿了,剪紙課不為剪紙,只是一個讓人放開一切雜務、內省思考、重拾初心、分享故事的機會。 「我們為了甚麼動手做事?為何出門工作?初心都是為了自己及身邊的人幸福,疲累挫敗都會令我們忘記了當初出發的原因。 」

His artworks, such as “Your Original Intention is the Most Beautiful Light (你的初心是最美的光)”from Taipei Lantern Festival, “Blessings from the Big Fish (大魚的祝福)”, “Tree of Life (生命之木樹)”, and “Come Take a Seat (有閒來坐)” (commissioned for the first Apple store in Taiwan), emanate a sense of joy and optimism. These pieces fill homes, galleries, and public spaces with vibrant energy, uplifting those who encounter them.

梅山太平:雲海的祝福(2018)

Yang firmly believes that art can serve others and inspire them, prompting him to extend his influence beyond his creations. Collaborating with corporations and organizations, he hosts paper-cutting workshops where he treasures the heartfelt stories shared by his students. From a boy naming his piece “Grandpa's Stick” as an expression of love for his grandfather to a girl dedicating her artwork to her single father on Mother's Day, these narratives underscore the profound impact of art on personal expression and connection. Yang encourages everyone to share their own stories, urging them to take a moment to reflect on someone they love, send blessings, and hold onto wishes nurtured in their hearts.

也許,當你有日感到灰心困頓時,不如也動動手,試一下剪紙。 就如楊士毅不斷重複所說的:「停一停,回想心中最想念的人,把祝福送出去,心願留給自己。 」

In the skilled hands of Master Hui Ka Hung, paper transforms into vibrant, lifelike creations embodying Hong Kong’s cultural heritage.

Hong Kong is a fast-paced city filled with innovation and potential. Among its towering skyscrapers are streets alive with people rushing to their next destination. Beyond the urban chaos lie alleys steeped in history and tradition. It is here that artisans preserve Hong Kong’s cultural heritage through traditional skills passed down for generations. Among them is Master Hui Ka Hung, whose workshop, Hung C Lau, has become synonymous with the art of paper craft.